It is a strange thing to have your competitive fire reignited, long after you have forgotten the heat of it.

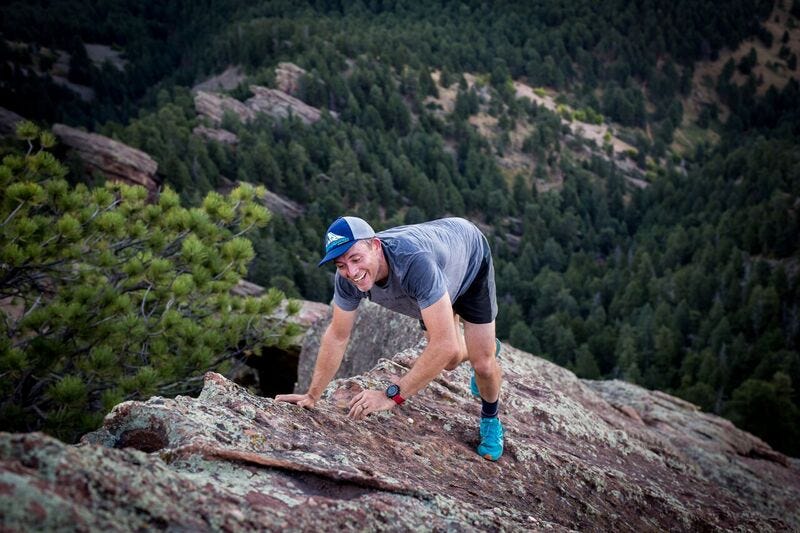

There are three established downclimbs from the top of “Stairway to Heaven” and I know all of them. I slowly, cautiously, and carefully descend the most direct of the three—the one that points you due North where the next rock is. Kyle Richardson flies past me via the East variation - although I had not met him before and didn’t mark it as interesting at the time that he should be anywhere near me so far into a foot race (he started late). When I reach the ground I stop and talk the person behind me through the moves—a common courtesy when scrambling in the Flatirons. The person behind me is Buzz Burrell, then in his mid 60’s. Another person of interest but in contrast to Kyle, Buzz was in my vicinity because he started early (about 35 years early). When Buzz arrived safely on the ground I started jogging toward the next rock (the 5th Flatiron). Buzz joined me, then passed me, then dropped me. I next saw him at the finish line comfortably enjoying a tasty beverage; sweat already dry on his skin. What the fuck!?

Thus sparked a long dormant fire.

Although I was aware I was in a race—I did not understand at first. I was not a runner, for starters. Competition as I defined it involved another person directly in front of me actively trying to impeded my movement. I was ill equipped to understand a race of any kind, really. A race across the Flatirons though? Terrain that involved movement most people define as rock climbing? I had entered a world so strange that my initial confusion can be forgiven. This was my first Tour de Flatirons, a race between members of the Satan’s Minions Scrambling Club (SMSC). I didn’t understand, but I would in time.

Legend has it the name was born from an email. Bill Wright had developed plans for a morning run in the Flatirons, but this predates such widespread knowledge of “scrambling” and the various Flatiron features and so he described the run in more prescriptive terms. About 5 miles, maybe 2,500 feet of vert during which we will cover about 10 pitches of climbing terrain. Back to the trailhead around 8:30am. The email was forwarded along, and when the description was read by someone that didn’t know Bill it was met with shock. I advise you to stay clear of this Bill Wright guy, he must be a Minion of Satan if he thinks he can do that before work. Bill knew he could do that before work. Bill was unusual, but not alone.

A small group was formed.

Another legend has it that Bill first began scrambling in earnest after breaking his back in a freak accident on Death and Transfiguration (a gorgeous 5.11b trad line deep in the Flatirons) in 1999. While cleaning the route, slack was introduced into his line when a side angled rope caused a cam to pop out. Things happened quickly after that, and he lost control of his brake strand (which he didn’t have hold of because he was still on belay). He plummeted 60 feet to the ground. When he eventually rose to his feet he tackled the Roach Top Ten—a hotly contested list of the ten best (easy) climbs in the Flatirons. In doing so (with Tom Karpeichik) he became the first person to complete them all in a single day, although 9 years prior the indominable and aforementioned Buzz Burrell had completed all but one, which he intentionally subbed for an even harder climb because he didn’t agree with the selection criteria.

Entry into the Satan’s Minions now requires (among other things) completion of all ten of these climbs, though not in a single day.

Another legend tells of Bill’s first time hearing that the 3rd Flatiron had been ascended in under an hour (car to car, by Jim Merritt) sometime in the late ‘90s and hardly believing it to be true. Further he then learned that Gerry Roach, a historically significant local legend (creator of the Roach Top Ten and many popular guide books), had the record for such an endeavor at “around 45 minutes”. At that time the fastest that Bill had gone was around 2 hours (with his wife Sheri!)—but although they had been going as fast as they could, they had used ropes. Bill’s wheels were surely turning.

In the fall of 1998 Bill and a few friends organized a race which would evolve over the subsequent decades into the Tour de Flatirons. Three young men (Bill, George “Trashman” Bell, and Ken Leiden) departed Chautauqua Park moving as quickly as they could to see what was what. Bill’s account of the race cracks me up. Trashman (Bill loves his nicknames) went first with a head start, carrying a rope for them to rappel off the back with. Bill notes that his time was supported, but adds that he thinks it only adds “about 5 minutes”—a claim he would likely dispute today. Bill and Ken took off together but eventually became separated by their relative fitness, and Bill actually got lost and wandered to the 2nd Flatiron on accident—the idea Bill Wright would get lost on the way to the 3rd Flatiron is the craziest part of the whole story for me. Somehow, he still beat Ken to the face and then employed a futuristic advantage to stay in front and catch Trashman: Bill did not use climbing shoes, even on this first ever Flatiron race. After making the rappels, Bill actually paused his watch to wait for Ken (about 4 minutes he said). When the two were reunited he started his watch back up and sprinted down, easily beating Ken who (insanely) ran back down in his climbing shoes! Bill finished in 47m9s, although pausing your watch and resting for 4 minutes is now considered against the rules (or ethics, just ask Bill!).

Legends aside, this is how I think it went down: Bill Wright really is Satan. A misunderstood dark angel. During his formative years he grabbed a rope and started climbing up toward the heavens. It is a long climb. He’s still working on it. Along the way he became fascinated with climbing faster, reasoning that the faster he climbed the higher he could get before he became too tired to climb any further. Eventually he chopped his rope in half during a devilish ritual designed to give him a greater power and strength. He studied at every dark altar, and learned all the tricks that the devil is said to have. Soon he had no rope at all. Others watched his progress. They felt compelled to follow this strange example. First it was two. Then four. Now over 200. And Satan saw all that He had made, and behold, it was very good.

Scrambling is a climbing term, which simply describes moving over technical terrain without a rope. Climbers actually have many words to describe this act (soloing, bouldering, 3rd classing, etc.) but scrambling is different because it implies that the terrain in question is easy. Those other terms imply the opposite, although to be fair that is not required and there is much nuance. You can solo a route or scramble it and which word you select may say more about you than the route itself. If I say that I scrambled a route, I am saying that the route was easy for me but also easy within the context of climbing at large. In other words it isn’t just easy for me it is easy for nearly any rock climber. If rather, I say that I solo’d a route I have removed the climbing community from my calculus and chosen to define the action within only my own experience OR I have placed the climbing community at the forefront of my calculus in the hopes I am not downplaying my action and encouraging an unsafe decision in another. Savvy? Yeah, me neither.

Another definition, which I tend to use often and prefer to the above ego laden complexity, is that scrambling applies to terrain on which I might completely let go with my hands and comfortably stay on the rock (before anyone gets cute—bat hangs and knee bars are not comfortable). Within the Flatirons of Boulder routes which meet this criteria are everywhere. There is no other collection of rocks like this in all the world, I believe.

Formed by some sort of geological activity 50 million years ago involving the Fountain Formation, conglomeratic sandstone and other super boring things of this nature; I prefer a more mythological history. I believe God formed the heaven and earth in six days. In the beginning it was dark and he/she/they turned on the light. Or else a different and more eloquently descriptive God made from which is not, that which is. It could’ve been a God who speaks almost exclusively in short riddles, a Mother of all things. Or Allah, for when he decrees a thing, he only says to it “Be” and it is.

Whichever God made this earth, and however long it took—after, they turned their eye elsewhere or rested. It was then, when the good and the grand weren’t paying attention that a Devil tilted the slabs to the sky. Just ask anyone that’s traveled along them. Each of us stood at the base of one of these rocks for the first time, an Angel on one shoulder and a Devil on the other.

Each of us knows which one we listened to.

There are five numbered Flatirons, although most people may not be aware of the Fourth and Fifth. The Fourth is the largest and weirdest. The most difficult is probably the Second, assuming you care about going to the top (like me) although this is debatable and an argument for the First would not be beneath me since I know many ways up the Second. The easiest might be the Third, although getting off the Third is not straight forward.

The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was to convince the world that these five Flatirons are all that exist.

Spanning several miles between Boulder Canyon and Eldorado Canyon, a multi-tiered wonderland is filled with hundreds of Flatirons. Most of them have an East Face at around 55 degrees. Behind and to the sides of nearly all of them exist some of the hardest and most photogenic climbs in Colorado. With proper enthusiasm it is actually possible to travel back in time here, swear to God. You can find yourself suddenly transported to a place without crowds, pollution, residential expansion, global warming, or even geriatric presidential candidates.

You can sweep thick Jurassic ferns from your face and peer across a valley to a massive rib of stone extending into the sky. You can dip a flask into a trickling creek, step carefully around poison ivy, and begin any adventure. You can learn the language of this place, where the secret trails are, where the water springs clean, where the lichen grows thick, where the rock is strong and where it is weak. With secret knowledge hard earned or shared in whispers one might scramble or climb here eternally and test any type of physical limit in pursuit of a beauty unique in all the world. Beauty only a Devil might conjure. A selfish brand, laced with vanity and pride and pain.

Bill’s somewhat impromptu race up the Third Flatiron in 1998 was repeated the following year, and then the next year, and then the year after that. By 2003 participation had shot up to nineteen young(ish) guys including Buzz Burrell, Jon Sargent, Stefan Griebel, Bill Briggs, and Tony Bubb. Names recognizable to any student of this strange sport. That same year Bill extended the race to include a second “Time Trial” (as he called it then) and some of the framework for the modern day race was starting to take shape.

The second race was up the First Flatiron, the most popular and beloved rock of all. In addition to the regulars, participants included climbing heroes Timmy O’Neill and Christian Griffith as well. Buzz won this race (and the one up the Third) completing the round trip in a record setting 35m04s. A stout time, even by today’s standards. The fact that I can find this time, as well as the story under which it was recorded is a primary ingredient to the longevity of this group. Bill has a knack for recording history*—although I should just say he has a knack for recording and over time the records have become historical.

*in fact, as an aside, Bill Wright is the first person to coin the term “Fastest Known Time” on an old web site he ran. Although, as he will tell you, he was just calling it the “Fastest Time” when his friend John Prater pointed out that it was actually just the fastest time that he knew. An FKT is now common parlance for basically any athlete in all manor of speed measured esoteric sports from cycling to rock climbing.

The First Flatiron “race course” doesn’t change much over time. Many of us can explain subtle ways in which it has, but largely those details remain unimportant. Anyone is free to test themselves against it at any time. There are many who do. I can recall my great pride when I first managed the round trip in 60 minutes. It took me many efforts. In addition to completion of the Roach Top Ten and among other things a “sub 60m” round trip time on the First Flatiron is now required to gain membership in the SMSC. It takes nearly everyone “many efforts” and that is the point, I suppose. Members of the SMSC and others like them have memorized the route so completely that they never need to pause and decide where to step or which hold to grab, a symptom of having repeated the route (literally) hundreds of times. The result is that they can make the round trip in 60m at something approaching a light jog. The fastest among them have gone about twice that fast. Fitness alone is not the only ingredient to this achievement. It takes time, care and desire. Just like learning any other craft the physical work of it is a secondary concern.

After Buzz set the record in 2003, next to lower it was another world class athlete and ultra-runner; Dave Mackey in 2004 logging a time of 33m19s. In Dave, the group suddenly had a professional athlete in his prime. I’ve heard many times about how his dominance inspired some of the less professional among them to begin training in earnest, and take things a bit more seriously. It took 6 years for the next lowering of the record. During that entire span Stefan Griebel was putting in work to become Dave’s equal. In 2010 he managed to lower the time to 33m05s.

Stefan is a local engineer and family man. I’m not aware of anyone quite like Stefan. He is not a professional runner, or climber and I say this with great love and admiration—you can tell when you look at him. In other words, he isn’t rail thin and made from mostly lung and leg. Neither is he laden with steel hard muscles and a gorilla-like flared upper body. Recently I noted that I could see some definition around his abs and when I pointed it out he told me “yeah, I just kinda stopped drinking beer a month ago and lost like 15 lbs.” Normal person shit. He mostly looks like a regular (if very fit) guy. He basically is a regular guy.

Until somebody starts a watch. Or hands him the rack.

In those types of situations he is the most irregular guy I know and there are few that can climb harder and run faster. His accomplishments are legion. In addition to that First Flatiron record, he also snagged the record for the Third, a combination of the two, the Fifth, and other lesser known Flatirons. He has records in Rocky Mountain National Park to this day including the much revered Longs Peak Triathlon (either solo or with a partner). He also has the record for the Naked Edge - a climb in Eldorado Canyon, about 600’ long and HARD 5.11b performing the round trip faster than nearly any other climber on Earth can get to the start of the route. Those are just a few of the things that I can recall off the top of my head, but I would venture to guess that not even he can remember all of the things that he has done faster than anyone else.

I have many favorite stories about Stefan, but for the subject at hand this one will suffice: fall, 2013 or so. Stefan reigns supreme in the Flatirons or at least he co-reigns alongside Dave Mackey who’s life and body altering accident is a few years in the future. Stefan is out for his favorite run: up the Direct East Face on the First Flatiron. He’s midway up the first pitch and happens to glance up and notice another scrambler isn’t too far ahead. Happens all the time, not a big deal. He’s going to pass this guy in a few minutes and hopefully have a nice friendly encounter. He knows he is going to pass him because he’s wearing jeans and has a backpack on. No further evidence is required. He puts his head down, and loses himself to the movement and flow he’s enjoyed countless times before and will enjoy for countless times again.

Soon, he notices that he hasn’t caught this other guy though, which is very strange. He looks around a bit with some concern, wondering if this poor guy has gotten lost or climbed into trouble somewhere strange. It takes him longer than it should to finally spot him, because he is in the last place he expected to see him: still on the route but now further ahead. That is unsettling. Nobody is faster than Stefan and certainly not in jeans. Stefan hits the gas.

Soon he’s going as fast as he can. Breathing hard and sharp, sweat pouring down his face, movements crisp and large. Yet… this guy remains uncatchable. Finally, he summits with the mystery man no longer in sight and already well into the downclimb. He doesn’t hesitate and launches into his well practiced dance down the backside of the Flatiron.

I’ll pause the story here for some brief context. While most Flatirons have a friendly, gradually sloped east face; this comes at the expense of a steep and often overhung west face. If you ascended without a rope, it can be difficult or complicated to get down. In some cases, a rope must be carried simply for the descent, or barring that the entire ascent route must be reversed. The First Flatiron has a downclimb which is steep, but not overly difficult. Most (but not all) of this downclimb meets the “no hands” definition of scrambling. A well traveled and fast person might take 5 minutes to get down from the summit. The fastest Minions have done it in less than 60 seconds, which is ludicrously fast.

Anyway—Stefan continued in pursuit. When he arrived on the ground, the mystery person had just finished stuffing his climbing shoes into his backpack and started to jog down the trail. Stefan gave chase. At some point, winding down the technical and rock laden trail, Stefan realized he was running as fast as he could and yet still he was not able to pass this guy. They sprinted to the finish in lock step, both of them grinning ear to ear.

After the two of them had caught their breath, Stefan invited him to participate in the next Tour de Flatirons race. In that race, or one soon after anyway, Stefan and the Mysterious Matthias Messner (sans jeans) effectively tied the FKT on the First Flatiron (33m06s & 07s - within the margin of error, as Stefan puts it). You either know Matthias or you don’t, and most likely you don’t. He isn’t famous or even mildly famous in the way some of these other folks are. He’s a sponsored and talented runner to be sure with his own collection of FKT’s, but also a dad and working stiff with a near-ceaseless, kind smile and a charming Italian accent.

Matthias would go on to lower the record down to 32m18s in 2015 and from there he would experience a two year streak of Flatiron dominance setting additional records for the Third Flatiron, The Quinfecta (all five numbered Flatirons) and winning the Tour in 2015 and 2016. Incidentally, 2016 was my first year participating in the Tour de Flatirons and I can attest that his dominance that year was so complete I believe he may have gotten bored. In the fall of 2017 however, Matthias suffered a bad accident on the Third Flatiron. He survived a massive fall while on the downclimb but suffered substantial injuries. Myself, along with Bill Wright and Stefan Griebel were with him when it happened and to this day I can no longer pass through that area without thinking about him. With luck, and that near-ceaseless smile, he made a full recovery and is still an absolutely phenomenal athlete. Although he has participated in the TdF since that accident, he has not achieved the same level of dominance that he once had. Partly, perhaps, because of the psychological burden he now carries—but at least as likely—because someone hungry and young is always around the corner.

By 2019 Kyle Richardson had already been a member of the SMSC for at least three years, but he was young and he was hungry. Comprised almost entirely of leg and lung, his kind heart beat a fire through his body which propelled him to a record that still stands now*, five years later (30m19s). He took nearly 2 minutes off the prior record, something I would’ve said was impossible had I not been there that day and seen it with my own eyes. King Kyle indeed.

*a quick historical note. The First Flatiron was completed in 29m22s last year (2023), but via a different and closer trailhead (by ray of sunshine personified, Skyler Williams during a TdF stage). A case could certainly be made that this is now the record although I am not making it here, because of the trailhead discrepancy.

The story of the continuously lowered time on the First Flatiron is a Satan’s Minion story. Every single record time was achieved by a member of SMSC, and most of them occurred during a race which was organized by Bill dating all the way back to Buzz’s 2003 record set during the first recorded race up the rock.

The Tour de Flatirons is now a staged race, held on consecutive weeks each fall with a unique and varied course each week. Bill is a fan of the Tour de France, and so the name and format was derived from cycling. I’m told. I’ve never watched cycling so can’t/won’t fact check that. Bill takes great care designing the courses, which can range from a single (usually iconic) Flatiron, to a complex and confusing enchainment of multiple Flatirons. Depending on the stage, participation has approached 40 people. Completion of the TdF requires a recorded time for every stage. This is an achievement which around 20-25 people now claim each year.

Courses are announced one week in advance. Most participants spend this week practicing the course. There are rules which require racers to remain on designated trails, except when they are on rocks or otherwise linking between them where no trails exist. Apart from this rule however, the course definition can never be specific or completely clear. The week leading up to the race is filled with hive-like activity, and racers probe the course for weaknesses or secret advantages. Seemingly inconsequential details are discussed at length. Rumors are spread about how one guy maybe found 3 seconds by moving 6 inches to the left at the first bulge of stone. Scouting parties are assembled to confirm. Measurements are taken. Strategies are formulated.

Still, each week someone usually gets lost. They take that trip back in time and become disoriented. They climb the wrong thing, or descend the wrong direction. The overall winner is unquestionably the fastest among them, however the next several in line are often the racers which are able to most consistently finish each stage without major error.

Each stage is wild and nearly indescribable. Someone (usually Bill) yells “GO!” and goddamn do they ever. Every stage involves some sort of uphill run at the start to get to the rocks, somewhere in the 10m-15m range. It is a grueling and sadistic affair. The length of the approach is such that a field of 20+ racers will spread out considerably. The fastest fly like the wind at a full gallop, appearing unbothered by the steep uphill terrain and rocky trails. Most will dance between a run or a hike as best they can, at war with gravity and that extra slice of pizza they probably didn’t need at lunch. Soon each racer finds themselves struggling for position with only one or two other people and by the time they get to the first rock an order has been loosely defined.

Going up a rock climb at speed sounds at first insane. Truly, it is nowhere near as crazy as it sounds. Mostly because of the word speed—which is not a good word here. Nobody is moving fast, not really. You may emerge from the thick forest alone, and taking your first look up the rock you may see 15-20 people in front of you, all within throwing distance. You may be unlikely to catch any of them. I’ve seen footage which is less entertaining than watching paint dry. Ants marching one by one, two by two, or whatever. Plodding slowly up a massive swath of stone. Silently performing some job or task with purpose and focus for reasons alien, strange, or irrelevant.

The first-person experience is not so easily dismissed.

When I hit the first rock, I’m aware of everyone in my vicinity. I know their strengths and weaknesses relative to my own. They may be more fit than me, or less. They may be better climbers than me, or not. They may be terrible at downclimbing or rappelling or perhaps they’re younger and more athletic so I’ll have no hope of staying in front of them on the next downhill run. All of this gets fed into my calculations, along with the minutia of the week’s worth of practice sessions. I plot my course, and attempt to pass the people that I must pass at the place where it is most beneficial to pass them. I’m aware of where on the rock nobody will be able to pass me, and so I use these areas to my advantage. Sometimes I place a foot or grab a hold with the care and specificity I usually reserve for sport climbing at my physical limit. Other times my feet follow my hands, and I slap the rock ahead without even a glance. Always my heart is screaming in my chest, begging for me to relent. I try so hard not to listen.

Sometimes I top out and grab a rappel line, strategically or because there is no other way down. I leap into the air and shoot down a rope as fast as I’m able. The heat builds from friction as my metal rappel device controls the speed of my fall. I burn my hands, my stomach, my legs—whatever touches this thing. A worthy trade off for a few seconds.

Other times I move directly into a complex but well practiced downclimb, strategically or because I’m something of a purist and avoid the rappel when I can (we must continue with style, after all). People may zip past me on the rap line, or they may not thanks to some unforeseen complexity or logistical snafu which ropes often have in spades.

Then it is a burst of chaos as I run downhill through the forest, upright by the will of a God and a Devil in equal measures. I leap over obstacles, fly past patches of poison ivy, spin around trees, and keep a watchful eye over my shoulder for would-be pursuers. All too often, I’m caught up and passed. All too often, I give in to my traitorous mind which whispers a false ideology about conserving some energy or effort for the end. Another rock comes and I repeat the ceremony anew.

Eventually I’m running back to the start drunk with exhaustion. Fear and doubt swallow my thoughts as I stumble, focusing all of my effort to maintain a speed which could be achieved by a small child. Someone may come into view ahead or behind and somehow—improbably—I redouble my effort. I squeeze every drop of what I have, then I dip back into the well and somehow find more.

It is a religious experience. Hail Satan.

In truth, this race is not now—nor has it ever been—the primary reason to gain access to this club. It is probably the most talked about, or the most celebrated, or the most well documented element of the group and so I understand when people associate the SMSC with speed and speed only. This is also the time of year which generates the most interest in membership. Bill has recently required that entry into the club be outside of the month during which the race occurs.

The truth is that only a small subset of members even participate in the race at all. An even smaller subset actually finish the entire thing. This is an estimate, but I believe the group currently has about 200 members which I can only measure by looking at the email list. So perhaps 10% of the members complete the race, or thereabouts. The race is fun, but the email list is the real benefit. It is a collection of like-minded people with similar interests, similar dispositions, and similar drive. It is a community, in short.

Bill has built this community. Because I am a member, I don’t have to try hard to find climbing partners (or running partners, or cycling partners, or scrambling partners or used gear or beta or whatever). I have at my disposal something I am coming to learn has great and immeasurable value. Friendships are harder to come by as an adult. Mostly they are built around a shared passion, assuming you happen to be lucky enough to have a passion in the first place. I know at least 200 people that share my same passion and are stylistically similar to me with respect to movement on technical ground. I do my best not to take this for granted. Many of my enduring friendships have been born from this small community.

I have, for my entire life, found a special joy when I meet someone I know out in the world unexpectedly. Like most of my quirks, I blame this on having grown up in a small town. Everyone out there whom I don’t know takes on a featureless, colorless, quality—my small town brain cannot deal with so much stimulus. When someone I know pops into the scenery, it’s like seeing in color all of a sudden. I have this experience nearly every time I climb or run anywhere near the Flatirons. I love it.

I owe Bill a great debt for this, and I will almost certainly be unable to pay it.

A while back, somebody commissioned some shirts. Like all of my clothing choices, I wear this shirt whenever it cycles to the top of the pile in my drawer. Sometimes I hesitate before I put it on though. There is some baggage that comes with it, and some people see it and respond in accordance with that baggage. Occasionally, I’m instantly told to pass by on an Eldo trade route. My speed is assumed, based on the shirt. That’s cool I guess, even if unwarranted. Other times though, I sense I’ve been boxed in. Beliefs and attitudes that I may not possess have been placed upon me.

As much as I value community, I rebel against conformity and those are two things which are necessarily at war.

There are those that don’t much care for the SMSC. I admit, sometimes they have just cause. There are three topics which—in my opinion and perhaps only my opinion—are a bit of a sore spot for this group.

Topic 1 - Elitism.

There is an inarguable and foundational component of all climbing which is colored by elitism. By the nature of the sport, each climber quickly and immediately ranks themselves among their peers almost as a matter of necessity. That’s not the attitude I think troubles the SMSC though, because they are out there “climbing” easy routes. The elitism comes from the fact that this activity is a blend of running and climbing.

From a climber’s perspective the easiest East face of the easiest Flatiron is not meaningfully different from most of the others. A pure climber would consider these routes a waste of time. They may not be interested in doing them quickly, but by and large basically any rock climber can climb any of the Flatirons. From a runner’s perspective on the other hand, every route is an ascent toward madness or certain death. A pure runner would consider these routes impossible or at the very least, extreme. And so there lies the rub. I can feel it baking off of everyone I meet out there. A belief is being placed upon me. An idiotic, and ridiculous belief: I think I’m better than them. They might also be into scrambling, which actually makes it worse because then they will have heard of SMSC and if I’m wearing the shirt my holier-than-thou attitude is more apparent.

That’s the nature of being in a club though, isn’t it? People in clubs all suck, basically. They think they’re so fucking cool, but you know what? They’re not! And so forth. I get it. It’s fair.

The worst part? This idiotic and ridiculous belief that has been placed upon me is totally accurate. I think I’m better than people that are confined to the trail way down below. Or that can’t scramble all of the coolest routes because they don’t have the wealth of knowledge I have accumulated or maybe they don’t have the skills to test something out with a rope first, or whatever. Perhaps someone hasn’t gained admittance into this group for any number of reasons which could be cultural or boil down to disinterest but which will be perceived as related to inadequacy. Even if I don’t perceive this myself, I will be perceived as perceiving it anyway. Because I’m in the club, and I suck.

I make it worse all the time. I admit to putting on a show at the base of a rock, sprinting up into the air while tourists gasp and shout. Elsewhere on the rock, with other scramblers all about, I’ll do the same thing by going ever so slowly through a more difficult or obscure section of rock that they can’t go - maybe clearing my throat or coughing a bit first. What a fucking attention whore. Oh, you guys are doing ‘freeway’? That’s cool. Me? No, haha, I’ll be off somewhere else - wherever the spirit takes me I guess - somewhere without crowds. I’ll see you later though, I’ll probably be jogging down that route when I’m done doing my more rad shit. Yeah, I meant to say jogging and down. Yeah, I meant to make you feel inadequate. Yeah, I suck.

In contrast, pure rock climbers tend to think this whole thing is fairly idiotic. Occasionally I’ll drop off the back of the Slab or Seal or Hillbilly (or many many other rocks) and talk shop with sport climbers I see there. We’re all climbers here, is the thing I try to convey I guess. No we’re not, is the thing that’s made clear. It is important that we all understand just who’s passion is ever so slightly less moronic. What a world.

Topic 2 - Gender.

The fairer sex also participates in this activity. They succumb to the fire of competition. They enjoy solitude deep within the confines of a land out of time. They enjoy friendships. They command respect for their athleticism and prowess. They climb harder and run faster than they thought they could, or they don’t—just like men. In fewer numbers, however. If you aren’t already thinking it; let me quickly insert a critique: I spent several paragraphs discussing the historical lowering of the First Flatiron FKT, and mentioned nothing of the female side which has it’s own parallel history and heroes. What a dick move.

Some late, and transparently apologetic compensation: I don’t actually know the first female time of note on the First Flatiron, but the first one that I really heard about was from the legendary Quinn Brett in 2016, who went round trip in 56m40s. Angela Tomczik lowered it to 50m46s in 2018. Sonia Buckley brought it to 47m29s in 2018 (I was there - it was impressive). Annie Weinmann brought it down to 43m20s in 2020. Lastly, Bailee Mulholland scratched out the current FKT in 41m06s from a sprint she made in 2022.

All of these women lowered these times alone, or at most with a small group of friends cheering them on. None of these times are from a race or competition. I’m not sure what to conclude from that.

Often the female champion of the TdF is the only female to finish. From the earliest days, the group had a bit of a PR problem. Bill had a web site in which he graded the various round trip times one might achieve for the Third Flatiron. The fastest is 40m, for which you were awarded the title of Satan. The slowest time listed is 3 hours, and for this you were awarded the title of “Chick Scrambler”. Not great. Bill acknowledges this. In fact, I’ve seen him have to apologize for it in person more than once because the web site is still functional (here) and is probably the first thing that pops up if you google Satan’s Minions Scrambling Club. Just like wandering around in Skunk Canyon can take you back in time, perusing this web site can bring you directly to the late 90’s. Bill has repeatedly and genuinely admonished himself for this, and promised to fix it. I’ve been hearing it for years now, yet it remains. With it, and perhaps other things I am immune or blind to, the group has a reputation for being a bit unwelcome to women.

I’m not sure that’s completely fair, but I am sure that I can’t speak on that for obvious reasons. I’ll just say that there could be other factors at play, but that I’m not going to wade into those waters here. Suffice to say; I have seen women dominate this activity with control and grace and strength—and they enjoy all it has to offer in all the ways the boys do.

Topic 3 - Elephants.

Ignoring the elephant in the room implies a willful neglect. Who could ignore such a beast? If, however, you live in that room? You see the elephant every day, and eventually it isn’t so remarkable to you. You can get used to anything, even an elephant. You don’t really ignore it necessarily, you just stop noticing it. This isn’t willful neglect at all, it’s complacency. It’s natural. People might come by and instantly remark “Yo! What the fuck is with the elephant?!” and you will be forced to reckon with the fact that your experience in this room has become unusual.

Myself and others like me experience “no-fall” terrain in an unusual way, and we do it so often that we occasionally forget this. No-fall terrain is a climbing term which I suppose is self explanatory, but in case it isn’t; this is a place which you simply cannot fall from. The result would be death. Most people (including many rock climbers) will never enter into such terrain. It is intentionally avoided, or else protected. Those that occasionally but somewhat rarely travel into it will do so with heightened senses and focus. Care will be taken. This type of attention to detail makes sense, of course. But it is not sustainable. You cannot maintain it indefinitely. Over time, you will become complacent. You will stop noticing the elephant.

I have stories of accidents, naturally. They often include highly competent, athletic, smart and experienced members of this group. Some of them were scrambling in the Flatirons. Some of them were scrambling elsewhere. Some of them were climbing with ropes, but still toying with this unusual relationship which they’ve formed with risk. Some of them died.

I didn’t really compete in last year’s Tour de Flatirons. My love for this sport did not measure up to my wife’s fear of it this time around. Her fear may or may not be justified, depending on your own relationship with risk. There has only been one accident of substance in this race, in all it’s long history. The result was a broken ankle. That complacency element? It is not present in a race, or at least that is my experience. Focus is present and in great supply, however. It is one of the beautiful side effects to participation. Focus like this is hard to come by.

That does not mean risk is not also present. Supposing I had to put a number on the likelihood that a catastrophic accident should occur, in which one or perhaps many people died during a Flatiron race—my number would be small, but it would not be zero. Given time, it will eventually happen. That’s just the math of it. A grim reality, but one shared with travel in a car or anything else for which the possibility of death is inherent, however small. I hope not to see this day of reckoning, but I already know what will happen when it comes. People will ask about that elephant, and how nobody seemed to be able to see it. There will be no explaining it, not really, and there will be no sympathy for anyone that can manage to live with an elephant.

After that first race, in which I had my desire for competition reignited, I began trying my hardest each week. Each week Bill Wright mopped the floor with me despite my efforts. It was close though. Close enough that we formed a bond that has remained through the years since, and evolved well beyond the Flatirons into a friendship.

I was adamant at first that I wasn’t interested in a mentor. I didn’t want our friendship to be transactional, because I understood I had little to offer save a smile or laugh from time to time. Bill is over 20 years my senior, and so he has a lot to teach. Whether I wanted a mentor was irrelevant, because I got one. I hope over the years since we met, and all the years remaining, that I manage enough smiles and laughs to make up for all that he has given me. I know that I probably wont. That’s ok. Friendships aren’t written up on a balance sheet and marked up in black or red.

Bill is directly responsible for the way I engage with the mountains. In basketball, people talk about coaching trees. Some great coach years ago had an assistant coach who had an assistant coach and so on down the line, such that a certain style or philosophy might be traced through time. Bill has a very large tree. It would be difficult to grasp the expanse of it.

Bill is not the first person to move quickly over complex technical terrain, but he was certainly an early adopter and perhaps the most public about it. He loves sharing what he’s done, and celebrating the things his friends have done. He has certain characteristics around which a community might be built. A humble excitement. The main character in a story which has him surrounded by heroes and giants of twice his own considerable strength. The devil, after all, is the one in the background leading from the shadows. Spend 20 minutes with Bill and you will end up with 19 minutes of non-stop chatter about something cool one of his friends did.

Bill has directly influenced the way that many people engage with the Flatirons, far more than he’s met or ever will meet. His influence extends beyond our great slabby range, on toward Eldorado Canyon, where people tie into short ropes and cries of “micro” can be heard more often than “off belay”. His influence extends worldwide, as members of the SMSC explore the wild regions of our beautiful planet. People see how they move out there. Questions are asked. Legends grow.

On a cool fall morning, 100 years from now, someone will be in the Flatirons. Relative tranquility will be interrupted ever so briefly by sharp and pained breathing. A group will arrive from just below. Perhaps by then the group won’t be comprised almost exclusively of white guys. One can hope. They will run past, then hop onto a rock without breaking stride. Thoughts will form in this person’s head as they watch. What a bunch of assholes. It was quiet a second ago and then comes this freight train of obnoxious assholes. OR. Those people must have a death wish.

The people in the group will be smiling. They are exactly where they want to be. Up high and relatively alone in this place of absolute beauty and wonder, their dark church. They don’t have a death wish. They want to live like this forever. They think about danger and death constantly. They are forced to confront tragedy on occasion—same as everyone else. 100 years hasn’t made it easier to explain.

When they finish, back at the parking lot somebody pops a tailgate. They have to get to work, but don’t want to leave just yet. The sun has set the Flatirons ablaze. Silence permeates the group as their eyes sweep across the expansive view. Lawyers, engineers, landscapers, carpenters, doctors, professional athletes, cops, criminals, wealthy, poor, young, old—all types—banded together by a shared love for this place.

An interloper walks up, and asks “are you guys the Satan’s Minions?”

They’ve heard the stories. Legends never die.

Nice tribute to Bill and to what you love.

Thanks Danny! But who is this "Tony Krupichka" guy? Doesn't look like he's pitching out anything...